Farming on the edge: new insights into farming in the urban fringe

There are multiple demands on England’s urban fringe, and land use within it is highly contested. In this context, farms can struggle to compete. However, we argue that greater support for farming in the urban fringe is a key part of making best use of this land in our increasingly urgent context of mitigating and adapting to climate change, restoring nature, improving public health and feeding people.

England’s urban fringe and its farms

Land around our towns and cities, on the urban edge, can face immense pressures for change: from development for housing and industrial sites to cutting through land for roads, railways and busways, pylons and other energy infrastructure.

Speculation drives up land values. Developers buy land or its rights, and proximity to urban areas mean developments such as golf courses, horse stabling and riding, as well as other amenities, are attractive options. In this mix, farming land to produce food – the main use of rural land in England – can struggle to compete.

The urban fringe debate focuses on the Green Belt – land protected in planning law and policy, with the aims of preventing urban sprawl and keeping land around towns and cities permanently ‘open’ or free of built development. The Green Belt is highly contested, and its integrity and purposes are under threat as it is ‘nibbled away’ bit by bit for individual developments. Recent changes to the National Planning Policy Framework (NPPF) introduced in December 2024 raise questions as to whether working farms within the Green Belt could be redefined as ‘grey belt’, thereby increasing the possibility of them being developed for housing. CPRE has previously reported extensively about development of Green Belt. The wider countryside and nature NGO movement has called for a long-term strategic vision for the Green Belt that would maximise its potential to solve complex problems for people, nature and climate, including contributing to a secure food supply.

In this report, we make the case for the relevance and value of farming on the urban fringe as a key part of this vision for maximising the potential of the Green Belt and other areas of the urban fringe and making best use of our finite land supply. You can view an interactive map of England’s Green Belt below, and a definition of ‘urban fringe’ follows.

What is the ‘urban fringe’?

We define the urban fringe as both Green Belt and ‘Comparator Areas’. Together the urban fringe covers 22% or just under 3 million hectares of land in England.

Green Belts are areas of land around towns and cities (there are 14 in total in England), which are protected in planning policy to remain open or undeveloped to prevent unrestricted urban sprawl. Examples include Oxford and Nottingham (see interactive Green Belt map below).

Comparator Areas are areas of land around urban centres (of more than 100,000 people) that are not covered by existing Green Belts. Examples include Leicester and Hull. A map of Comparator Areas can be found in a previous CPRE report here).

Despite arguments to the contrary, the urban fringe is as farmed, and at least as green (if not greener) as the rest of England as a whole in terms of natural and semi-natural land use. One-third of broad-leaved and mixed woodland, over a third of standing open water, and over a fifth of conifer woodland is within England’s urban fringe.

England’s Green Belts

Please note ‘Comparator Areas’ are not included in this map.

Importance for UK food security

Urban fringe farmland makes a significant contribution to overall UK food supply, providing 20% of all cereals and around 10% or more of many major food groups. Although urban fringe land can often appear scruffy or neglected, beneath the surface the soil quality is disproportionately good relative to the rest of the UK, and it is essential not to dismiss this potential. We must instead support current farmers and encourage new farming initiatives to bolster food production and security in these areas.

Number of people fed

The most basic analysis of urban fringe land shows it makes up 21% of the national farmed area of England or, extending this to the UK’s 17.436 million hectares (ha) of farmed land area, then 10.7%.

If urban fringe farmland is used productively then in broad terms this land could provide food equivalent in value to over three fifths of the food needs of 7.24 million people.

Quantity and value of food produced

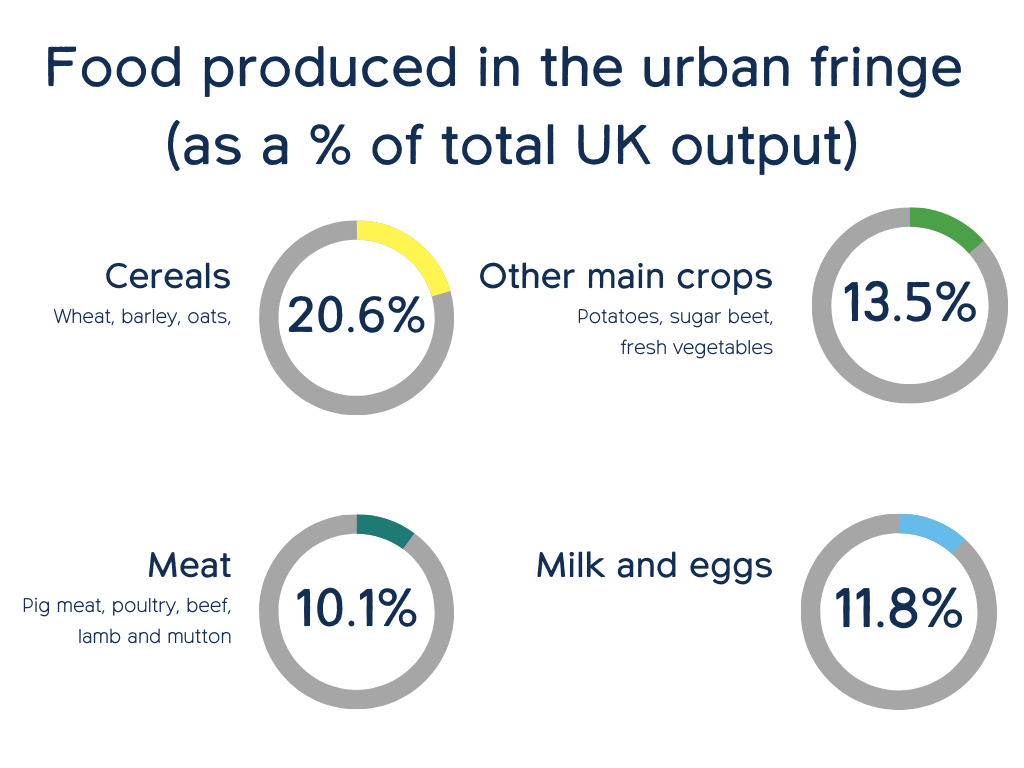

Our analysis considers levels of UK domestic production as a percentage of total supply for major foodstuffs produced. On this basis we estimate that as a proportion of the new food supply in the UK urban fringe areas provide:

- over 20% of all cereals – wheat, barley and oats – for milling flours, brewing and distilling and animal feed

- from 9% to 15% of multiple major foods including pigmeat (9.3%), poultry (9.8%), mutton and lamb (9.9%), eggs (10.4%), beef (11.4%), fresh vegetables (11.5%), dairy (liquid milk 13.3%), potatoes (14.3%), and sugar beet (14.6%). Fresh fruit produced in the urban fringe is much lower at (3.4%); this reflects the small contribution domestic production makes overall to UK fresh supply of fruit which relies mainly on imports

The charts on the left summarise these stats. Average production percentages (against total UK output) have been calculated across the food products in each group to form the figure in each circle. Please see the full report for the data tables and full figures.

Quality of urban fringe soils for food growing

Our understanding of land, its soil quality, and what land is best to grow food crops on in England comes from the Agricultural Land Classification (ALC) system – a long-standing science-based model which classes land based on the potential to produce a range of crops with high yields on a regular basis.

Soil quality depends on long-term factors like underlying rock, stoniness, weather, and moisture levels—not just land management. It can only be permanently damaged if topsoil is removed or contaminated, such as by heavy metals.

Even neglected urban fringe farmland often retains its potential for food production. However, these high-quality soils need stronger protection in urban fringe areas, where development pressure risks stripping, sealing, or capping soil—permanently reducing its ability to grow food and provide other environmental benefits.

Urban fringe land is highly significant in UK terms

Urban fringe land has soil quality comparable to other farmland in England but holds greater relative value in the UK, where England’s land is better suited for crops than the other three UK nations, which are more grassland-dominated. Comparing soil quality across the UK is challenging due to varying grading systems and limited up-to-date data. Instead, we analysed cropped areas in each country as a share of overall farmed area from June Agricultural Census results for 2021. By amalgamating the results across the UK and comparing this to the urban fringe, we arrive at an initial estimate of the relative importance of urban fringe land to UK land in general for growing crops.

Cropland is relatively scarce in the four nations apart from in England where nearly half of farmland is under crops. As we know soil quality (as measured by the ALC mapping) in the urban fringe is similar to England as a whole and high shares of cereals and other crops are produced there (according to farm holding and farm type data). On this basis, we estimate the urban fringe area is much more important for crop production than its overall share of UK land: representing nearly 18% of all croplands for around 11% of the UK’s farmed land area. Given that the best land will normally be used for crops to get the best return and highest reliable yields, this confirms that urban fringe farmland is, at more than one sixth of the UK’s crop growing area, hugely important for the UK’s domestic food supply.

Trends in urban fringe farming

The amount of land used for farming in urban fringe areas is decreasing, with much of this loss occurring in the Green Belt. At the same time smallholdings increasing in number, with the potential to increase diversity and positively impact the urban fringe farming landscape. Overall, however, there is still much we do not understand about the reasons for these changes, and further research and support is needed to ensure that urban fringe farming is protected and able to thrive.

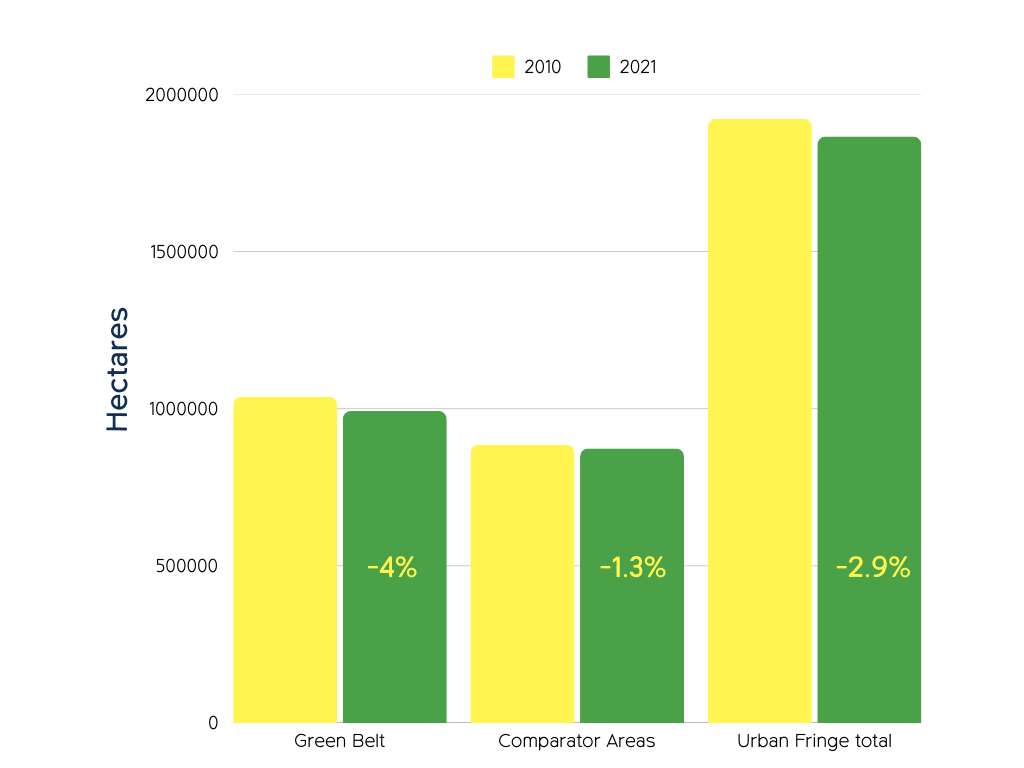

Urban fringe farmland is decreasing

The farmed area of England increased by 1% during the 2010s (not shown), but the urban fringe farmed area fell by 3%, or over 56,000ha (560 km2), an area equivalent to a city the size of Leeds, with much of this (45,000ha) reduction taking place in the designated Green Belt. See full report for data tables and national (England) totals, which are not represented in this chart.

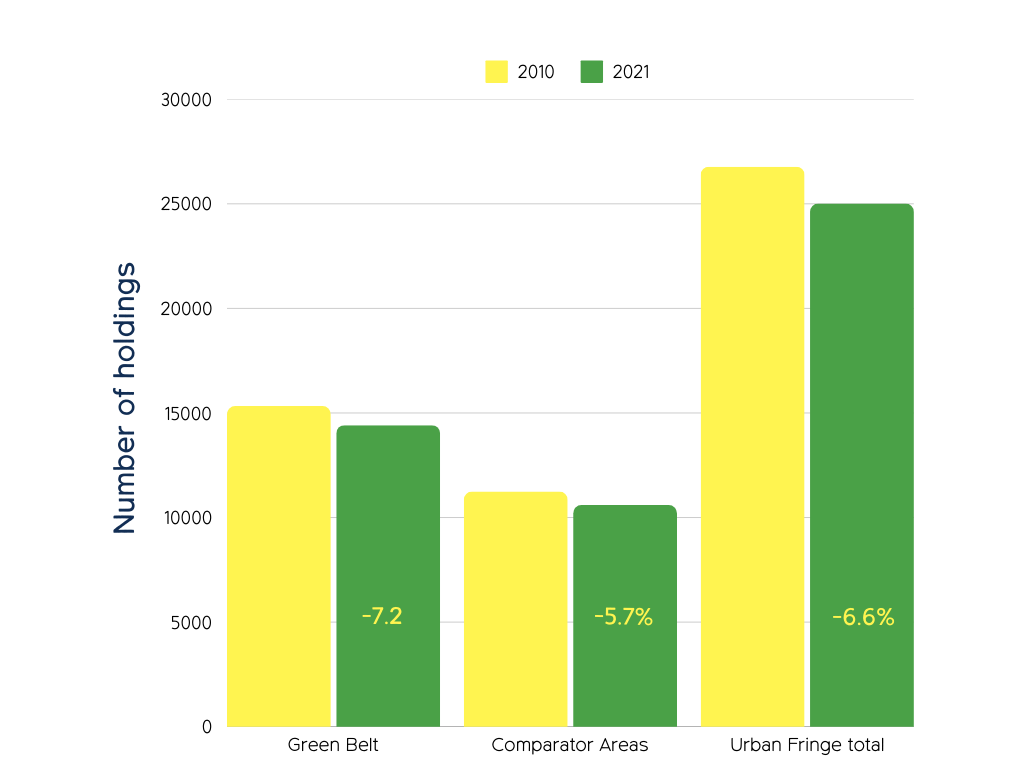

The number of farm holdings is decreasing

There has been a worrying decrease of nearly 7% in the number of farm holdings since 2010. The overall figure masks the difference between Green Belt and other urban fringe holdings with Green Belt faring comparatively badly. In relation to England overall, this supports the view that there is greater pressure on urban fringe holdings. See full report for data tables and national (England) totals, which are not represented in this chart.

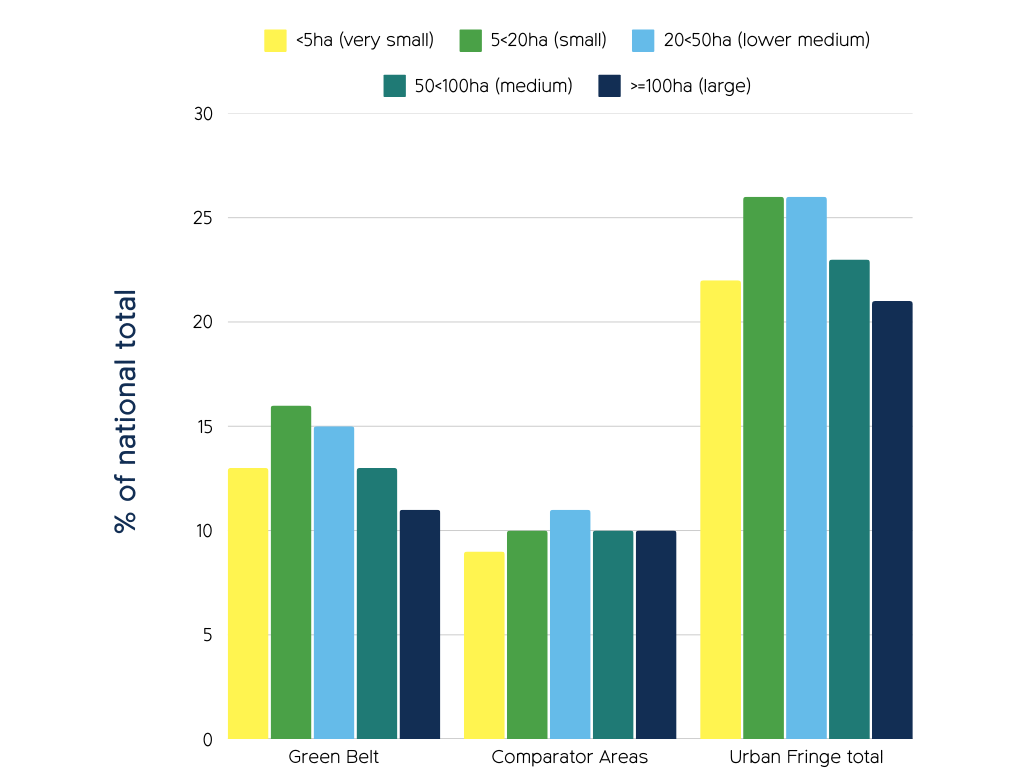

There are more small and very small farm holdings in the Green Belt

The number of large farms (above 100hs) in urban fringe areas is similar to the national average. Small to medium sized farms (below 100ha) are more common in Green Belts than other countryside areas, suggesting Green Belts support SME farms, though the reason is unclear. See full report for data tables and national (England) totals, which are not represented in this chart.

Green Belts surround major towns and cities, potentially aiding farm viability by providing access to many customers. Farms diversifying into direct sales or services like stabling may find less need for consolidation into larger units.

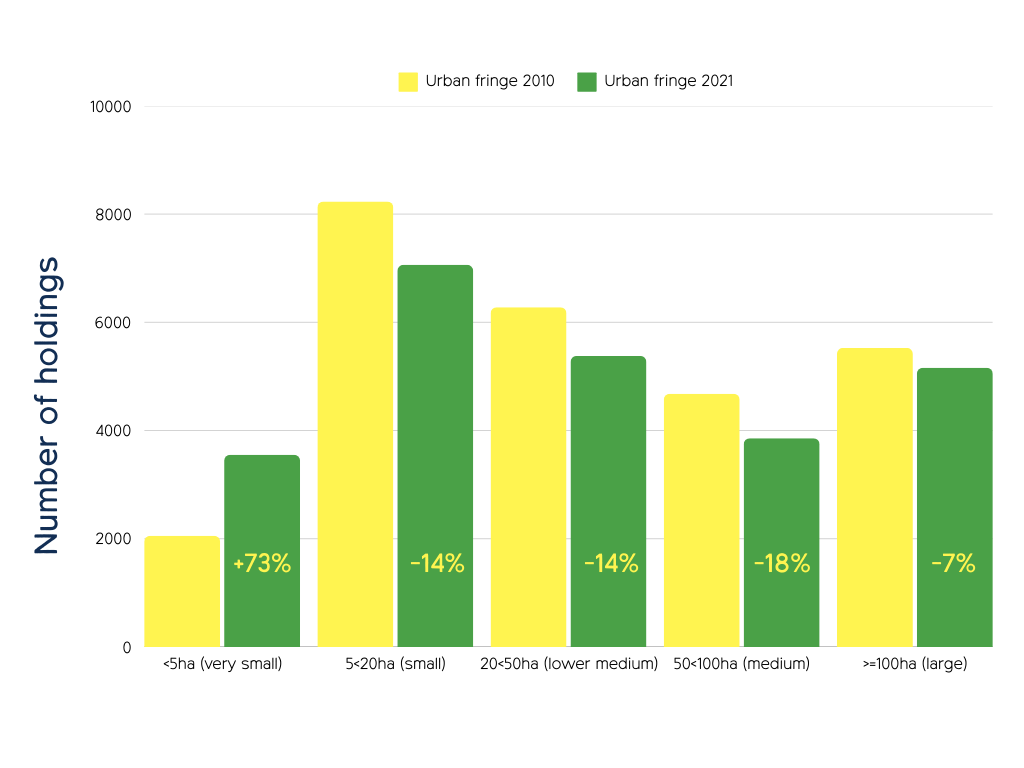

Huge increase in the number of smaller farm holdings and loss of larger farms

Although numbers of urban fringe farms have declined in recent decades – with the biggest losses noted in small to medium sized farms – this fall has now stabilised. Despite an overall rate of decline, very small farms have bucked the trend, rising in numbers more recently, reflecting a similar rise in national figures. Frustratingly, we lack a clear explanation for the statistical data, which makes it difficult to target support for the farms that need it most. See full report for data tables and national (England) totals, which are not represented in this chart.

Explaining the rise in very small farms is complex. ‘Micro farms’ may emerge as SME farms break up or sell land. Medium-sized farms face economic strain — they are too large for niche markets, and too small to compete in commodity markets with thin margins. The decline in large farms aligns with data on farm mergers, with fewer farms over 100ha but an increased area of 330,000ha from 2010 to 2021. Similar trends may occur in urban fringe areas, yet the net loss of 1,700 farms there remains unclear.

Government data highlights a key gap: no explanation for these changes or their drivers means that it’s less useful for policy and targeted support.

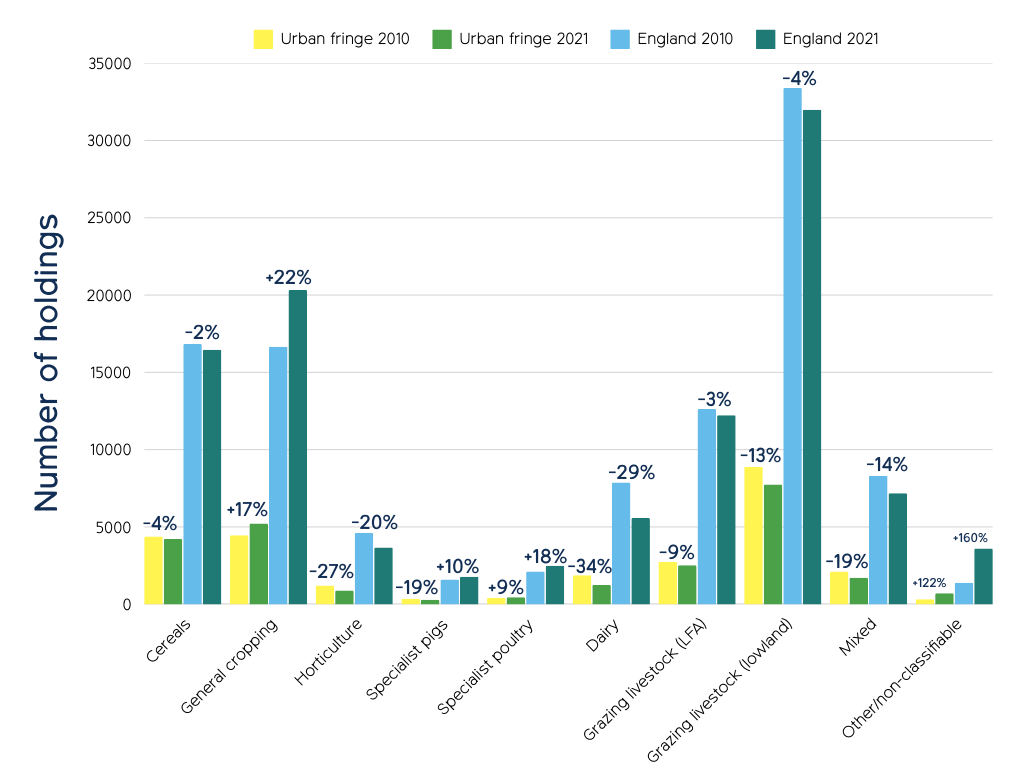

High proportions of horticultural, livestock and mixed farms are being lost in urban fringe areas

Between 2010 and 2021, there were large changes in the types of production farms specialised in across England, with general cropping seeing one of the biggest increases (up 22%) and dairy the largest decrease (down 29.2%). Overall, these (national) changes are reflected in the urban fringe, but there were bigger losses for each falling farm type, particularly cereals, grazing livestock and horticulture, and smaller increases. For specialist pigs there was a loss of urban fringe farms against a national trend of increasing number of holdings overall. See full report for data tables.

National trends are mostly reflected in urban fringe areas but with generally more intense decreases, and subdued increases. This reflects a fall in urban fringe farms overall, with similar shifts from farming to general cropping and ‘Other’ non classifiable types observed both in the urban fringe and nationally.

Numbers of dairy, horticulture and mixed farms have fallen dramatically since 2010, both nationally and in the urban fringe. Dairy farms are down nearly a third nationally and horticulture holdings down a fifth. Mixed farms also fell by 14%. This decline was notably greater in urban fringe areas, reflected in falling numbers of urban fringe farms more generally.

Significant drop in UK vegetable production

Since 2011 there has been a notable fall in vegetable production in the UK which may shed light on the identified falls in horticultural enterprises in the urban fringe. Furthermore, and concerningly, the rate of change appears to have accelerated sharply since 2021. See ‘Table 8’ in the full report for more.

For supporting data tables for the charts above, please read or download the full report here.

Previous trend analysis of farming on the urban fringe

Drawing on previous analysis (from 2006) we can speculate on reasons for the more recent changes in urban fringe farming. These include: the knock-on impact of wider societal changes (such as the development of major infrastructure); the need and appetite for other activities to supplement financial income (e.g. stabling, education); and the impact of local food networks.

Recent years have seen little analysis of urban fringe farming trends and support needs. The most in-depth study, nearly 20 years old, remains the key reference. Revisiting it provides context for recent findings, showing a continued decline in urban fringe farming, as confirmed by 2010–2021 government data.

Reasons for land use change away from farming

The 2006 study found three key factors determining whether land use had changed away from farming in the period between 1990 and 2006:

- The size and level of financial support for certain farm types with larger farms and cereals, dairy, sheep and beef farming proving more resilient than other unsupported types of farming such as horticulture, pigs and poultry.

- The collapse of market gardening around urban areas – often on more vulnerable smaller holdings – which further fragmented who owns and manages urban fringe land.

- The development of major infrastructure disrupted land holdings and the compulsory purchase and loss of land could shrink farms to a size which is no longer viable.

The nature of urban fringe farms

The study found that urban fringe areas were very different from each other but that some trends were true for all areas:

- There were fewer commercial farms than national figures, and farm sizes became smaller closer to the urban edge.

- Farms relied heavily on other activities to support the farm financially with horse related businesses most popular (e.g. stabling, riding).

- Around a quarter of farms were processing farm produce for sale locally, but for the majority most of their income came from selling in the national or international market.

Opportunities for urban fringe farming

The study identified several areas of opportunity for urban fringe farming to help further objectives of government policy at the time:

- Processing farm produce for local markets – 60% saw it as a benefit of their location.

- Realising greater uptake of environmental payments to farmers – in 2006 just under half (47%) of interviewees were in the main agri-environment scheme, Countryside Stewardship (now replaced by the Sustainable Farming Incentive – SFI), although uptake was lower nearer the urban edge.

- An appetite from urban fringe farmers to generate further income from providing public access and recreation as well as offering education and school visits.

These opportunities will likely remain. Urban fringe farms can tap into nearby populations, though recent research on local food networks is lacking. Supermarkets still dominate food retail. With direct area-based payments to farmers being cut, agri-environment schemes are now vital for farm financial support.

Strengthening farming on the urban fringe

The issues that are preventing urban fringe farming from evolving and thriving are multitude: from planning system issues to a lack of clear understanding of the drivers of change, these failures need our attention if changes are to be made. Our recommendations to strengthen farming on the urban fringe include improved policies, targeted support for farmers, and further data collection and analysis to better inform next steps.

The Land Use Framework (LUF)

Issues: The planning system is the main public policy tool that influences how urban fringe land is used spatially but is poor at taking account of the value and multiple benefits of farming. This means farmland best suited to producing food can be lost to other uses potentially in perpetuity. We lack the strategic tools and the framework to guide good local decision making.

CPRE recommends that the LUF should:

- Provide strategic oversight of the total land available and needed for a secure supply of food under sustainable land management.

- Identify urban fringe areas as priorities for supporting nature and sustainable land management.

- Update the evidence on the location and productive properties of farmland through the Agricultural Land Classification system.

- Strengthen policy protections for high-quality land.

- Encourage local authorities, through strategic land use plans, to bring forward new models for large scale landscape enhancement in urban fringe countryside that does not already benefit from being part of a national or regional park or National Landscape.

The Farming and Countryside Programme – environmental land management

Develop and promote a targeted urban fringe land management package

Issues: The new ELM schemes, in development since 2016, are now fully rolled out but remain voluntary and lack targeted measures for urban fringe farmland. CPRE research shows Green Belt areas are underrepresented in these schemes, missing a key opportunity to benefit nearby urban populations.

Removing the 5ha threshold for agri-environment schemes in 2024 should help smaller organic farms access ELMs, but barriers remain. Hectare-based measurements don’t suit diverse small farms, and applying for multiple actions is impractical. Small farm owners may be unaware of schemes, deterred by complexity, and lack affordable professional advice.

CPRE recommends that the Farming and Countryside Programme should:

- Promote a targeted Sustainable Farming Incentive (SFI) package for urban fringe farming to support sustainability and public benefits.

- Set a goal for 70% ELM scheme coverage on urban fringe farmland, maximising public benefit.

- Provide an attractive small farm package of bundled-up actions to make SFI easy to enter for nature-friendly smallholdings, especially market gardens and community supported farms (CSAs). This could reward actions that work in combination on such holdings, such as green manures, companion crops, wildflower strips, agroforesty and hedgerow management, with one area payment for the holding and the package.

National Planning Policy Framework (NPPF) and national planning guidance

Issues: Although the NPPF emphasises sustainable development, it does not fully recognise the value of nature-friendly farming in maintaining Green Belts and urban fringe farmland. It also overlooks the multiple environmental benefits these farms provide.

The NPPF aims to protect ‘best and most versatile’ farmland for its productivity, but this policy has weakened since the 1990s. Soil and land quality are no longer key factors in planning decisions, leaving the best farmland vulnerable despite its importance for national food security.

CPRE recommends that the government should further revise national planning policies and guidance to:

- protect, support and encourage sustainable nature-friendly farming enterprises in the Green Belt and wider urban fringe for their contribution to sustainable development; and

- Provide stronger protection for farmland, particularly high quality farmland

Government data on farming

Issues: Defra’s June farm surveys lack data to guide policy and funding, especially for urban fringe and rural areas. We still lack a clear understanding of:

- How commercial farmland is managed and its sustainability.

- The use and purpose of non-commercial land.

- Why farms move into different forms of crop/livestock production or out of food production altogether,

- What other services including environmental goods and services farms deliver beyond food output.

In such areas there is an urgent need to better understand the issues, to identify threats and opportunities for the sector and determine what measures could better support it to grow and thrive.

CPRE recommends that the government expands data collection on urban fringe trends, farmer decisions, and business behaviour, to improve policy targeting and spending efficiency.

Read report in full

You can read or print the full version of the ‘Farming on the edge’ report by downloading the PDF here.